Vienna 100 years ago on the eve of the outbreak of The Great War. Vienna’s cafe society, cosmopolitan atmosphere and intellectual life was attractive to an eclectic bunch of people (and some of the greatest future tyrants ever to be seen).

by Andy Walker

In January 1913, a man whose passport bore the name Stavros Papadopoulos disembarked from the Krakow train at Vienna’s North Terminal station.

Of dark complexion, he sported a large peasant’s moustache and carried a very basic wooden suitcase.

“I was sitting at the table,” wrote the man he had come to meet, years later, “when the door opened with a knock and an unknown man entered.

[……]

The writer of these lines was a dissident Russian intellectual, the editor of a radical newspaper called Pravda (Truth). His name was Leon Trotsky.

The man he described was not, in fact, Papadopoulos.

He had been born Iosif Vissarionovich Dzhugashvili, was known to his friends as Koba and is now remembered as Joseph Stalin.

Trotsky and Stalin were just two of a number of men who lived in central Vienna in 1913 and whose lives were destined to mould, indeed to shatter, much of the 20th century.

It was a disparate group. The two revolutionaries, Stalin and Trotsky, were on the run. Sigmund Freud was already well established.

The psychoanalyst, exalted by followers as the man who opened up the secrets of the mind, lived and practised on the city’s Berggasse.

The young Josip Broz, later to find fame as Yugoslavia’s leader Marshal Tito, worked at the Daimler automobile factory in Wiener Neustadt, a town south of Vienna, and sought employment, money and good times.

Then there was the 24-year-old from the north-west of Austria whose dreams of studying painting at the Vienna Academy of Fine Arts had been twice dashed and who now lodged in a doss-house in Meldermannstrasse near the Danube, one Adolf Hitler.

In his majestic evocation of the city at the time, Thunder at Twilight, Frederic Morton imagines Hitler haranguing his fellow lodgers “on morality, racial purity, the German mission and Slav treachery, on Jews, Jesuits, and Freemasons”.

“His forelock would toss, his [paint]-stained hands shred the air, his voice rise to an operatic pitch. Then, just as suddenly as he had started, he would stop. He would gather his things together with an imperious clatter, [and] stalk off to his cubicle.”

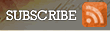

Presiding over all, in the city’s rambling Hofburg Palace was the aged Emperor Franz Joseph, who had reigned since the great year of revolutions, 1848.

Archduke Franz Ferdinand, his designated successor, resided at the nearby Belvedere Palace, eagerly awaiting the throne. His assassination the following year would spark World War I.

[…….]

“While not exactly a melting pot, Vienna was its own kind of cultural soup, attracting the ambitious from across the empire,” says Dardis McNamee, editor-in-chief of the Vienna Review, Austria’s only English-language monthly, who has lived in the city for 17 years.

“Less than half of the city’s two million residents were native born and about a quarter came from Bohemia (now the western Czech Republic) and Moravia (now the eastern Czech Republic), so that Czech was spoken alongside German in many settings.”

The empire’s subjects spoke a dozen languages, she explains.

“Officers in the Austro-Hungarian Army had to be able to give commands in 11 languages besides German, each of which had an official translation of the National Hymn.”

And this unique melange created its own cultural phenomenon, the Viennese coffee-house. Legend has its genesis in sacks of coffee left by the Ottoman army following the failed Turkish siege of 1683.

“Cafe culture and the notion of debate and discussion in cafes is very much part of Viennese life now and was then,” explains Charles Emmerson, author of 1913: In Search of the World Before the Great War and a senior research fellow at the foreign policy think-tank Chatham House.

“The Viennese intellectual community was actually quite small and everyone knew each other and… that provided for exchanges across cultural frontiers.”

[……..]

“You didn’t have a tremendously powerful central state. It was perhaps a little bit sloppy. If you wanted to find a place to hide out in Europe where you could meet lots of other interesting people then Vienna would be a good place to do it.”

Freud’s favourite haunt, the Cafe Landtmann, still stands on the Ring, the renowned boulevard which surrounds the city’s historic Innere Stadt.

Trotsky and Hitler frequented Cafe Central, just a few minutes’ stroll away, where cakes, newspapers, chess and, above all, talk, were the patrons’ passions.

“Part of what made the cafes so important was that ‘everyone’ went,” says MacNamee. “So there was a cross-fertilisation across disciplines and interests, in fact boundaries that later became so rigid in western thought were very fluid.”

Beyond that, she adds, “was the surge of energy from the Jewish intelligentsia, and new industrialist class, made possible following their being granted full citizenship rights by Franz Joseph in 1867, and full access to schools and universities.”

[…….]

Alma Mahler, whose composer husband had died in 1911, was also a composer and became the muse and lover of the artist Oskar Kokoschka and the architect Walter Gropius.

Though the city was, and remains, synonymous with music, lavish balls and the waltz, its dark side was especially bleak. Vast numbers of its citizens lived in slums and 1913 saw nearly 1,500 Viennese take their own lives.

No-one knows if Hitler bumped into Trotsky, or Tito met Stalin. But works like Dr Freud Will See You Now, Mr Hitler – a 2007 radio play by Laurence Marks and Maurice Gran – are lively imaginings of such encounters.

The conflagration which erupted the following year destroyed much of Vienna’s intellectual life.

The empire imploded in 1918, while propelling Hitler, Stalin, Trotsky and Tito into careers that would mark world history forever.