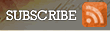

This year marks the 100th anniversary of World War I. This conflict has disastrous consequences for the Austro-Hungarian Empire. After the war, the Habsburg domains were divided up into independent nations. Now some people in these successor nations have nostalgia for the former ruling family.

But now, a disastrous century on from these seismic events, some in the former Habsburg lands are having second thoughts about the hasty disposal of the dual monarchy. A certain lingering nostalgia has begun creeping into Central Europe, where the greatest tragedies of a post-empire world unfolded. Among academics, it has become fashionable to argue the virtues of the strange, incoherent Habsburg state — to claim that, rather than being seen as backward and oppressive, Habsburg rule should be interpreted as an early model of how to run a modern, multinational body politic, one that even contains lessons for today’s European Union. Amid arguments about Scottish, Catalan, and Walloon autonomy and so on, others are looking to the Habsburgs — who would have viewed these independence movements as one among many “routine crises” to be dealt with through bribes and arrests — for insight.

Meanwhile, many citizens of the Habsburg successor states recall the monarchy with rose-tinted fondness. The dynasty’s sacred sites, such as Franz Joseph’s palaces in Vienna and Franz Ferdinand’s castle at Konopiste in the Czech Republic, swarm with visitors in pursuit of a more graceful and leisured time, with all of them happily oblivious to how few of them would have been allowed anywhere near these places when they had been up and running, and how genuinely stuffy, pampered, and peculiar the Habsburgs really were.

[…]

Of course, this is not something felt across all their former empire — but even those in many Slavic areas, while raised to despise the Habsburgs, are crushed with nostalgia for a patently better time. And in modern Hungary you see the distinctive shape of the old pre-1918 map on everything from walls to bumper stickers, reminding modern Hungarians in potentially dangerous ways of the many regions once under their rule. This nostalgia is particularly poignant now in western Ukraine (the former Habsburg province of Galicia), where old Habsburg towns such as Lviv are frantic to associate themselves with the West: Historically themed cafes play up their Austrian roots and decorate their walls with portraits of Emperor Franz Joseph.

Of course, it is not surprising that the Habsburgs should now have reputations that show a few green shoots. The world they ruled over was an incomparably better one than that which emerged from the 1914-1918 disaster.

The past always looks better when its more distant.