As the author states, democracy was introduced into Japan and Germany at the point of a gun after those two nations were utterly devastated and had to submit to foreign occupations. No such thing has ever happened to any Islamic nation. “Nation building” in Iraq and Afghanistan never had a chance in hell of succeeding. The analogies to Munich 1938 are interesting but often misleading.

by Bruce Thornton

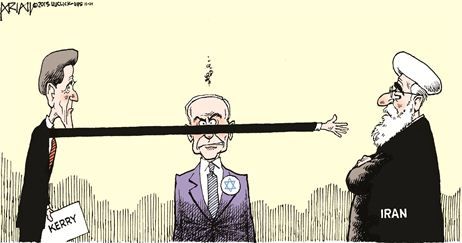

During the recent foreign policy crises over Syria’s use of chemical weapons and the Obama administration’s negotiations with Iran, the Munich analogy was heard from both sides of the political spectrum. Arguing for airstrikes against Syria’s Bashar al-Assad, Secretary of State John Kerry warned that the nation faced a “Munich moment.” A few months later, numerous critics of Barack Obama’s diplomatic discussions with Iran evoked Neville Chamberlain’s naïve negotiations with Adolph Hitler. “This wretched deal,” Middle East historian Daniel Pipes said, “offers one of those rare occasions when comparison with Neville Chamberlain in Munich in 1938 is valid.” The widespread resort to the Munich analogy raises the question: When, if ever, are historical analogies useful for understanding present circumstances?

Since the time of the ancient Greeks and Romans, one important purpose of describing historical events was to provide models for posterity. Around 395 B.C., Thucydides wrote that his history was for “those inquirers who desire an exact knowledge of the past as an aid to the understanding of the future, which in the course of human things must resemble if it does not reflect it.” [……..]

Both historians believed the past could inform and instruct the present because they assumed that human nature would remain constant in its passions, weaknesses, and interests despite changes in the political, social, or technological environment. As Thucydides writes of the horrors of revolution and civil war, “The sufferings . . . were many and terrible, such as have occurred and always will occur as long as the nature of mankind remains the same; though in severer or milder form, and varying in their symptoms, according to the variety of the particular cases.” [………]

In contrast, the modern idea of progress––the notion that greater knowledge of human motivation and behavior, and more sophisticated technology, are changing and improving human nature––suggests that events of the past have little utility in describing the present, and so every historical analogy is at some level false. The differences between two events separated by time and different levels of intellectual and technological sophistication will necessarily outweigh any usefulness. [……]

An example of a historical analogy that failed because it neglected important differences was one popular among those supporting the Bush Doctrine during the conflicts in Iraq and Afghanistan. The Bush Doctrine was embodied in the president’s 2005 inaugural speech: “The survival of liberty in our land increasingly depends on the success of liberty in other lands. The best hope for peace in our world is the expansion of freedom in all the world.” Promoting democracy and political freedom in the Middle East was believed to be the way to eliminate the political, social, and economic dysfunctions that presumably breed Islamic terrorism. Supporters of this view frequently invoked the transformation of Germany, Japan, and the Soviet Union from aggressive tyrannies into peaceful democracies to argue for nation building in the Muslim Middle East.

Natan Sharansky, a former Soviet dissident and political prisoner, used this analogy in his 2004 book The Case for Democracy, which was an important influence on President Bush’s thinking. Yet in citing the examples of Russia, Germany, and Japan as proof that democracy could take root in any cultural soil, including in Iraq and Afghanistan, Sharansky overlooked some key differences. Under Soviet communism, a highly religious Russian people were subjected to an atheist regime radically at odds with the beliefs of the masses. Communism could only promise material goods, and when it serially failed to do so, it collapsed. As for Germany and Japan, both countries were devastated by World War II, their cities and industries destroyed, the ruins standing as stark reminders of the folly of the political ideologies that wreaked such havoc. Both countries were occupied for years by the victors, who had the power and scope to build a new political order enforced by the occupying troops. As political philosopher Michael Mandelbaum reminds us, in Germany and Japan, democracy was introduced at gunpoint.

In Iraq and Afghanistan, neither of these important conditions existed when U.S. forces invaded. The leaders of these countries are Muslim, thus establishing an important connection with the mass of their people. Unlike Nazism and communism, which were political fads, Islam is the faith of 1.5 billion people, and boasts a proud, fourteen-centuries-long history of success and conquest. For millions of pious Muslims, the answer to their modern difficulties lies not in embracing a foreign political system like democracy, but in returning to the purity of faith that created one of the world’s greatest empires. Moreover, no Muslim country has suffered the dramatic physical destruction that Germany and Japan did, which would illuminate the costs of Islam’s failure to adapt to the modern world. Finally, such analogies downplay the complex social and economic values, habits, and attitudes––many contrary to traditional Islamic doctrine––that are the preconditions for a truly democratic regime.

More recently, people are invoking the Munich analogy to describe the Syria and Iran crises. But these critics of Obama’s foreign policy misunderstand the Munich negotiations and their context. The Wall Street Journal’s Bret Stephens, arguing that Obama’s agreement with Iran is worse than the English and French betrayal of Czechoslovakia, based his assessment on his belief that “neither Neville Chamberlain nor [French prime minister] Édouard Daladier had the public support or military wherewithal to stand up to Hitler in September 1938. Britain had just 384,000 men in its regular army; the first Spitfire aircraft only entered RAF service that summer. ‘Peace for our time’ it was not, but at least appeasement bought the West a year to rearm.”

Stephens, however, is missing an important historical detail that calls into question this interpretation. France in fact did have the “military wherewithal” to fight the Germans. The Maginot line had 860,000 soldiers manning it––nearly six times the number of Germans on the unfinished “Western Wall” of defensive fortifications facing the French—and another 400,000 troops elsewhere in France. Any move east by the French would have presented Germany with a two-front war it was not prepared to fight. Nor would Czechoslovakia have been an easy foe for Hitler. As Churchill wrote in The Gathering Storm, the Czechs had “a million and a half men armed behind the strongest fortress line in Europe [in the mountainous Sudetenland on Germany’s eastern border] and equipped by a highly organized and powerful industrial machine,” including the Skoda works, “the second most important arsenal in Central Europe.” Finally, the web of military agreements among England, France, Poland, and the Soviet Union was dependent on England backing France, which would not fight otherwise, and without the French, the Poles and the Soviets would not fight either. Had England lived up to its commitment to France, Hitler would have faced a two-front war against the overwhelming combined military superiority of the Allies. And he would have lost.

The lessons of Munich, and its value as a historical analogy, have nothing to do with a material calculation. Rather, the capitulation of the British and the French illustrates the perennial truth that conflict is about morale. On that point Stephens is correct when he writes that Chamberlain and Daladier did not have “public support,” and he emphasizes the role of morale in foreign policy. A people who have lost the confidence in the goodness of their way of life will not be saved by the material superiority of arms or money. And, as Munich also shows, that failure of nerve will not be mitigated by diplomatic negotiations. Talking to an enemy bent on aggression will only buy him time for achieving his aims. Thus Munich exposes the fallacy of diplomatic engagement that periodically has compromised Western foreign policy. Rather than a means of avoiding the unavoidable brutal costs of conflict, diplomatic words often create the illusion of action, while in reality avoiding the necessary military deeds. For diplomacy to work, the enemy must believe that his opponent will use punishing force to back up the agreement.

This truth gives force to the Munich analogy when applied to diplomacy with Iran. Hitler correctly judged that what he called the “little worms” of Munich, France and England, would not use such force, and were only looking for a politically palatable way to avoid a war. Similarly today, the mullahs in Iran are confident that America will not use force to stop the nuclear weapons program. Iran’s leaders are shrewd enough to understand that the Obama administration needs a diplomatic fig leaf to hide its capitulation to their nuclear ambitions, given his doubts about the rightness of America’s global dominance, and the war-weariness evident among the American people. [……..]

The weakening faith in American goodness that afflicts millions of Americans, and the use of diplomacy to camouflage that failure of nerve and provide political cover for the leaders charged with protecting our security and interests, are a reprise of England and France’s sacrifice of Czechoslovakia in 1938. That similarity and the lessons it can teach about the dangers of the collapse of national morale and the risky reliance on words rather than deeds are what continue to make Munich a useful historical analogy.

Read the rest – The lessons of Munich